Siegfried - Part Five

From Immigrant to International Fugitive, the Life and Death of a Man of God

X.

On June 29, 1976, one year and twelve days after signing his new contract, Sandra Geldhausen reported to counselor Mike Short at the Lakeland Counseling Center in Elkhorn that her thirteen-year-old son Ryan, an altar boy at St. Andrews’, had been molested by Fr. Siegfried while on a fishing trip.

*

Mike Short called the new Archbishop, Bob Sampon. Sampon called the Archdiocese ombudsman, Reverend Donald Weber. Donald Weber called Widera and scheduled a meeting. They met on July 1, 1976, exactly three years after Siegfried had been pulled over outside of Fredonia Township with his pants around his ankles. During the meeting, Siegfried admitted to what he called “a slip.” He was two months shy of completing his three-year probationary term for the felony in Port Washington. This meant that Siegfried Widera was in violation, and bound for Waupun. According to Weber’s notes, Widera was “shook” by the discovery. Weber wrote that he told Siegfried, “I would try to keep the lid on the thing, so no police record would be made.” Siegfried pleaded with Rev. Weber not to tell Otto and Gertrude. Weber complied.

*

Weber scheduled a meeting with Mike Short. He learned a common story: Sandra was recently separated from her husband. She and Ryan were new to the Delavan area. Ryan Geldhausen had trusted Siegfried and had seen him as a stand-in for his biological father. The priest had taken some of his altar boys on a fishing trip at the beginning of June. Sandra declined to tell Weber what exactly happened, but she said her son no longer trusted priests or the Church. The boy now suffered from a spiritual crisis. Short also said that Sandra Geldhausen feared reprisals from parishioners if she were to go to the police. In Short’s estimation, if the parish were to remove Widera immediately and offer some form of compensation for the boy’s counseling, Sandra Geldhausen would not contact law enforcement.

*

The next day, Leo Graham called Don Weber at his office. Weber detailed the conversation as follows:

Leo did not know what had happened but was greatly concerned that if Fr. W. leaves state during this probationary period, he could be picked up and immediately sent to prison without any further court trial. Graham is the de facto probationary officer. Has seen Widera weekly for past 3 years. Graham feels that if Fr. Widers [sic] must be sent to hospitalization, it must be within State (at least during next 60 days)—Leo doubts value of in-patient treatment however. If Geldhausen will not approach police, Graham suggests that Fr. W. remain in Delavan—at least temporarily. He suggests that I offer services of the Archdiocese for a one shot evaluation of the boy (to determine if there be any traumatic damages (usually in these cases, there is not.)

*

The ombudsman laid out to Dr. Graham “the Archbishop’s agenda.” Contact = Widera, then Short, then Mother, etc.

*

On July 7th, Weber and Graham met again. Graham told the ombudsman that Widera was deeply depressed.

*

The psychologist said that one “slip-up” in three years was not so bad.

*

The next day, Weber met again with Mike Short and was introduced to a new victim. The boy, “a mature lad of ten years” Weber wrote, had been molested during the same fishing trip in June. The victim’s mother said she wouldn’t go to the police but that she wanted Widera removed from the parish immediately. She said the incident left her disillusioned with the Church. Weber offered to cover any costs for the boy to see Leo Graham. He also promised the mother that he had spoken at length with the psychologist about counseling services for Fr. Siegfried. “I did not reveal that Fr. W. had been seeing [Graham] for 3 yrs. already.”

*

On the ninth, Donald Weber met Siegfried Widera at an Elkhorn restaurant. Weber told Siegfried to stay away from little boys. Delavan was a small town, and it was likely that rumors had already begun to spread. He also told Widera that the Archdiocese was working on relocating him, possibly, this time, out of state. They’d have to wait until his probation ended. For one, a term of the probation made it impossible for Siegfried to leave Wisconsin for any reason. For another, his probation officer was a church member; if Siegfried were to be relocated, even in-state, the officer would have questions—questions the Archdiocese could not answer. The lead pastor at St. Andrew’s, Father Henke, was quite old, stodgy, and uncompromising. Weber felt it imperative for the aged priest not to find out about this. Widera agreed.

*

It didn’t matter. By August 20th, Henke learned of the incident through gossip. He called the new Personnel Director, Father Waldbauer, who told Henke that it was indeed true. Henke immediately called for Widera to be removed from his parish.

*

August 20th was a panicky day for Donald Weber. In the morning he learned that Henke had called for Widera’s removal. He had no idea whether Henke had alerted authorities. Widera wasn’t answering the phone; he was nowhere to be found. Not knowing what steps to take next, Weber called Leo Graham. Graham told Weber that Henke hadn’t gone to police—not yet. Graham had some good news, he said. Siegfried’s probation had officially ended on the sixteenth—four days earlier. It was over. Weber could relax: the Archdiocese had escaped seeing one of their priests incarcerated by a matter of hours.

*

That night, Otto Widera drove the sixty miles to Delavan and helped Siegfried move his belongings into storage. Otto was now seventy years old. This was to be the last fatherly act he undertook for his youngest son. He never spoke to Siegfried again.

XI.

In late September, Paul Esser of the Personnel Board told Don Weber he was no longer comfortable with Siegfried Widera in a priest’s role. Father Esser’s stance was beyond late and proved, that afternoon, beside the point. Weber received a call from Leo Graham that afternoon. Widera was gone. He’d left Wisconsin on August 23rd, one week after his probation ended. He was living with his brother John in Costa Mesa, California. It appeared, Graham told the ombudsman, that Widera was considering a new life for himself, one that did not involve the priesthood. If this were true, it brought relief to the Archdiocese of Milwaukee. Though Widera had not held a pastor role for some time, he was still incardinated, which meant he was their responsibility. Having him out of the state and no longer interested in the priesthood meant their nightmare had come to an end. But Siegfried’s relocation had not been so simple or clean.

XII.

Widera got rid of his now-infamous red Volkswagen van, replacing it with a brand new red Ford Granada. Sometime that summer he drove his new car over to the Glendenning’s house in West Allis. After their night together at Willy’s, Patricia viewed the priest as wrongfully accused—a good man with a troubled past who was misunderstood. He was a victim in his own right. She welcomed him into the home. Randall was now sixteen. He’d recently received his temporary driver’s permit. He hadn’t seen Siegfried in nearly four years. Father Sig told the family he was leaving Wisconsin for California, where he’d accepted a position in a new parish. This lie was probably meant to put Patricia at ease before his next request, which was for Randall to accompany him to the West Coast. The boy could help Siegfried with his things and assist in the long drive. The ruse worked. Patricia agreed.

*

They spent nearly four months together on the road, leaving West Allis for California in no rush. In fact they initially traveled east so that Siegfried could show Randall the Mackinac Bridge. They came down in Upper Michigan, in St. Ignace, Siegfried’s Granada glinting in the sun. They stopped in Sault Ste. Marie before entering Canada and traveling Highway 17 up around Lake Superior. They moved further north before turning westward; they drove through Manitoba and Saskatchewan and rested, finally, at the far northern edge of the Rocky Mountains at Banff National Park. They stayed at the park for a while, perhaps two weeks, hiking and camping and cooking their meals by campfire. They reentered the United States in a rural area of Washington State, possibly through Osoyoos since there is a lake there and Siegfried preferred to be near bodies of water. The pair drove down through Washington into Oregon and the northern counties of California. They took turns driving. The trip must have been the happiest time in Siegfried Widera’s life. He was as far away from his parents and his past as he had ever been.

*

Three days before Randall Glendenning was to begin his junior year of high school, Siegfried purchased a plane ticket for him, bound for General Mitchell International. He drove Randall to John Wayne Airport. He stole a kiss and tearfully said goodbye.

*

Randall later told authorities the two had sexual contact roughly three times per week, or 33-times over the course of the trip. These incidences happened in motels along the backcountry highways Widera preferred in his travels. They also occurred at random intervals along the sides of turnpikes, when Widera, overcome with desire, would pull the Granada onto the shoulder of the asphalt. As had been the case when Randall was ten years old, Siegfried would have the teen press his thighs tightly together; then, Widera would insert his penis between them to simulate penetration.

*

After the road trip, Widera mailed a collection of photographs he’d taken of Randall back to West Allis. He’d written the locations and dates on the backs.

*

Sometimes he’d call Patricia Glendenning. Over the years, the calls became less frequent.

*

In 1984, Randall received a Christmas card from the priest. That was the end of it.

*

When asked by investigators, Randall said the molestation ended because Widera moved to California. “That’s the only reason it stopped.”

XIII.

John Widera was recent to California. Before moving to Costa Mesa he’d lived in Houston, Texas, where he began a company called Action Box. Action Box offered custom corrugated boxes, industrial packaging, floor displays, ballot boxes, and an assortment of manufacturing packaging. Now he was opening a new branch called, unimaginatively, the California Box Company.

*

(On a website for one of his companies, John Widera states, “I consider myself a true entrepreneur and not a follower, joiner or politician.” He has also self-published a number of books, including 2008’s Swimming with the Paper Whales: A Compilation of Experience, Knowledge, Thoughts, Articles, Essays, Facts, Data and Concerns Gathered from my Lifetime Journey in the Paper Industry.)

*

Otto Widera insisted on a close-knit family. They knew nobody in America when they’d arrived. They knew nothing of the culture. He feared for his family. By 1976, that family had all but disintegrated—not from an enemy but into the country itself. Otto no longer spoke to Siegfried, and John and Kristel did not speak with Ernst. Siegfried wrote, “It is interesting that the children do not get along with each other now. I am the only one that is on speaking terms with all of them [siblings]. We do not get together too often and if we do, it is not for very long. I have always wondered what caused this separation. We love each other the greater the distance we are apart.”

*

No evidence exists to support the claim Siegfried made to Patricia Glendenning that Ernst had molested him or treated him improperly in any way. There does, however, seem to exist a rift between Ernst and the rest of the Widera children. For a time, the eldest son and Kristel had both been employed by the University of Illinois-Chicago—Kristel in financial aid and Ernst as an engineering professor. He remained there until the 1980s when he became chair of a newly created Mechanical Engineering Department. By then, however, Kristel had come to work for her brother John’s growing box and supply business. The relationship between these three of the four Widera siblings can only be speculated upon in part because none of them will speak publicly. But this much is known: in the wake of Otto’s disowning of Siegfried, both John and Kristel came to the aid of their wayward brother.

*

Siegfried moved in with John in September. The house in Costa Mesa was five bedrooms, two-stories, a bright stucco façade with two Italian Cypress trees in the front yard alongside three tall palms that spread their fronds like fingers trying to touch the clear blue sky. Davis Elementary School was less than a mile south. Siegfried took one of the spare rooms. John had been married for seven years and had small children. Likely John kept the particulars of Siegfried’s past legal and sexual issues a secret from his wife and daughters. An employee for John later said that the girls bossed Siegfried around, and he cowered to them. “Siegfried will do whatever [John’s] family tells him to do.”

*

By October, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee’s Priests Personnel Board had not heard a word from Fr. Siegfried. This worried them. They reached out to Dr. Graham and conceded how crucial he was to their future dealings with Widera. “Knowing how delicate this matter is, the Personnel Board has agreed to ask your consultation in our dealings with Father Widera in the future. Respecting your necessary professional confidentiality, we wonder if there is any information or suggestion that you might make that could assist the Board in its communication with him.” The Archdiocese had all but lost control of Fr. Siegfried.

*

Two weeks after receiving the letter, Dr. Graham responded. “You are correct in assuming that Father left St. Andrew’s Parish in Delavan for a much-needed vacation in California. In light of the intensity level of the rumors in Delavan, it seemed wise not to have Father Widera physically present in the community to serve as an ongoing stimulus to the local gossipers. I had been in touch with Father Widera for the first two or three weeks that he had been in California, but I had not been for the last two or three weeks. I am also not in possession of any address at which he could be reached or telephone number where he could be called. This is because Father always called me collect.” Graham went on to tell the Personnel Board that he did not expect, necessarily, to hear from Siegfried again—though he didn’t not expect it, either. “The problem with all of this is that I have lost touch with Father Widera.” He told them to reach out to Otto to obtain a physical address for John. Graham continued: “I can fully sympathize with the problem facing the Personnel Board. If the allegations against the Father were proven to be true, and with a previous history of conviction on a similar charge, Father Widera would be a very difficult priest to place in a parochial position within the Archdiocese of Milwaukee…I have suggested this much to Father, and it is a fact of life which he readily accepts. Father himself has mentioned the possibility of staying on the West Coast in a non-sacerdotal occupation, at least for the time being.”

*

Graham closed the letter by recommending that Widera’s mental health and the “corporate mental health of the Archdiocese” would both be better off if Siegfried no longer pursued a career in ministry.

*

Otto Widera must have given the Personnel Board a good phone number for his son. On October 27, 1976, the new Executive Secretary, Rev. John J. Waldbauer, discussed with Siegfried his options moving forward. These were reiterated in a letter sent to Siegfried two days later. “The Personnel Board recommends a choice,” Waldbauer wrote. “First, that you pursue significant counseling to assist you in coming in touch with yourself about the action that has brought about a hasty exit from your last two assignments.” The other option was for Widera to “be released to the services of another diocese; with the permission of the Archbishop, you would request to minister elsewhere.” He reminded Widera that his status with the Archdiocese was “delicate.”

*

Siegfried chose the latter.

*

On Widera’s thirty-sixth birthday, Archbishop Cousins penned a long letter to Bishops William R. Johnson and Michael Driscoll of the newly established Diocese of Orange, in Orange County. The letter is manipulative and misleading. In the six or so weeks following the letter from Dr. Leo Graham, it would appear that Cousins had spoken to Widera on at least one occasion, and that Widera—now in desperate need for money; his leaving Milwaukee had come with the stoppage of his health insurance and other benefits—wanted to return to ministry. Cousins placed a fine shellac over Widera’s past:

Father Widera…has done good work for the Diocese [of Milwaukee] in the places to which he was assigned. In his earlier years there was a moral problem having to do with a boy in school. This seemed adequately confronted through treatment and intense desire upon Father’s part to avoid any repetition of a similar offense…More recently, however, there has been a repetition, and according to our State Laws further psychiatric treatment is mandated with the strong recommendation that no immediate assignment be made in the environs of the Archdiocese.

Father Widera has cooperated in every way and is presently under treatment…[It] has already been arranged [that] a doctor in California will take over at this point. From all the professional information I can gather there would seem no great risk in allowing this man to return to pastoral work.

Cousins closed the letter by asking that Widera be offered part-time work that “would give him the support of living in residence with other priests.” If Johnson and Driscoll could accommodate this request, “half the problem would be licked.” Cousins then asked the Diocese of Orange to consider a personal interview with Widera after the New Year.

*

On January 10th, 1977, Father Michael Driscoll wrote to Siegfried Widera that he had been appointed to a post of Associate Pastor at St. Pious V Church in Buena Park, California.

*

“Let’s face it, Sig,” ombudsman Don Weber wrote in a letter of congratulations, “a change in geography isn’t going to change the person. But, perhaps a change in professional care could be of great assistance to you.”

XIV.

Father Siegfried was incardinated into the Diocese of Orange on November 23, 1981. In mid-December, the Chancellor of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, Robert G. Sampon, wrote a letter to nearly every Church body in Milwaukee including the archdiocesan newspaper, The Catholic Herald, to inform them of the news. He ended the letters: “Kindly remove his name from your records and responsibilities.”[1] It was a whitewashing.

XV.

Less than two months into his tenure at St. Pious V Church, the Diocese of Orange restructured the parish, and Fr. Siegfried was transferred to St. Justin Martyr in nearby Anaheim. The transfer was completed on April 11, 1977—the Monday after Easter. At St. Justin, he was immediately put in charge of Youth Mass. A note in the church bulletin announces the first meeting of such for April 14. “All the youth of this parish are cordially invited to attend and bring a friend. Fr. Widera will be the celebrant.”

*

He served in this capacity at St. Justin for four years.

*

The letter in which Donald Weber warned that a change in geography would not bring about personal change also urged Widera to continue with counseling. “I met one of the priests of your diocese at the Convention I was attending. Without revealing too much data, I did ask him to pay you a visit and to help you feel at home…Perhaps he could recommend a good psychologist.” Despite the suggestion, Widera did not seek counseling in California. He told the Bishop of Orange he saw no reason. He had had no personal problems since the move. California itself was therapy. He’d never lived in a place so sunny and beautiful. He played golf year-round and hiked and swam. Getting away from the long, bleary winters of Wisconsin and from Otto had cured the priest.

*

Bishop Driscoll agreed. He contacted the Archdiocese of Milwaukee about incardinating Siegfried into the Diocese of Orange. The Archdiocese of Milwaukee were more than happy to oblige.

*

Siegfried Widera left St. Justin Martyr in Anaheim sometime around the end of 1981. He was assigned to St. Edward in Dana Point. Widera described his new post as “one of the most beautiful spots on earth for a church.” Once again, however, Widera found himself at odds with a dominant male figure. “There is no heaven on earth,” he concluded about Dana Point. “The pastor had a heart attack in the first months I was there. I supposedly ran the parish, but even from his ICU bed, he was in control. After three years, I decided I could not survive another year in Dana Point, and so, I asked for a transfer.”

*

He was assigned to Immaculate Hearts of Mary in Santa Ana. He called this new post “a city barrio” and “a culture shock.” He said he hadn’t much to do in Santa Ana. “I got to know a couple altar boys who wanted to be priests (and I believe they probably will).”

*

“After the year,” Fr. Siegfried wrote, “I went to Yorba Linda, up in the hills, a new parish without a school.” His appointment in Yorba Linda did not last long. “While there,” he explained, “I had promised my former parish altar boy captains a trip. We went to a doctor’s swimming pool. This was reported, but I personally believe nothing happened. Then, in my new parish I re-met a family I knew in my second parish in Anaheim. Being in a new parish and territory, I stopped by their home often. She was divorced for two years. I knew her family for eight years (played golf with [redacted]). After a while, I became involved with her three boys. Since they were seeing a counselor about the divorce, one of them mentioned me, and so I was reported…At present time, there is no legal ramification, but in the near future there might be a warrant out for my arrest.”

*

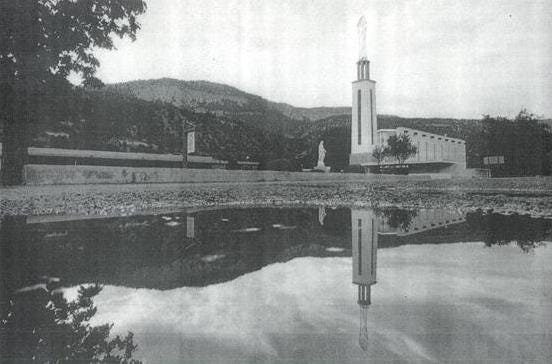

On September 24, 1985, the Diocese placed Widera on sick leave. Less than a month later, Siegfried wrote the above personal history from a tiny room at Villa Louis Martin, in Jemez Springs, New Mexico.

[1] The letters sent by Sampon are identical except for the one sent to the Herald. In it, Sampon included a postscript: “This is not for the OFFICIAL COLUMN.”